The mark lingers down the years, a fuzzy, yellowing vision rendered in Instagram sepia. Sunlight warming closed eyelids. The sound of the breeze in the tall grass, a creased copy of The Wind In The Willows nearby, the pages fluttering. The smell of suncream, freshly cut grass and salt and vinegar. Afternoons stretching on and on for ever. Dreamtime.

"As adults, time is lost," Tim Walker tells me. "We're all so busy and everything is accelerated. What a child has is a lot of time to wander and daydream. That's what I did as a child."

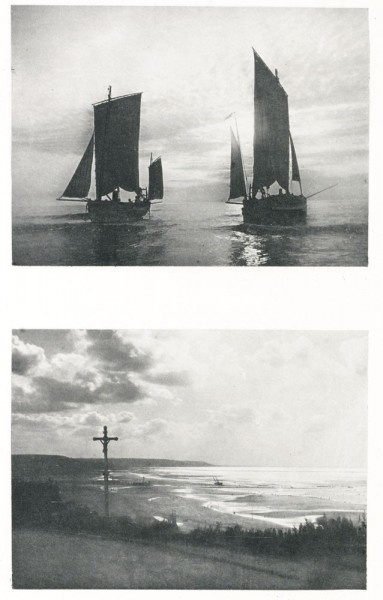

It's what he still does. Walker is a photographer. He takes photographs of models and clothes for magazines such as Italian Vogue and W. Some of the most recent have been gathered together in a book called Tim Walker Story Teller. I suppose you'd call them fashion pictures. But, really, they're daydreams on paper. Summer fresh and storied. Photographs of a woman sitting in a biplane made of baguettes. Photographs of a UFO gliding over a country fence in the middle of a hunt. Photographs of country houses and beds and Spitfires and blow-up see-through sailing ships. They do what the best fashion photography does – take you somewhere new.

"I love beautiful clothes," admits Walker. "Clothing takes my breath away when it's exquisite. But fashion is something that's not my leading direction as a photographer. I don't actually care for fashion, but I do care about beautiful clothes. And when you're working for Vogue you see all these designers and then the stylist says, 'What about this dress?' And you go, 'That really is a beautifully made dress.' You don't want to do anything else but photograph it. Fashion for me is just a massive dressing-up box. There's always something black, there's always something baggy. In fashion there is always something you can mix together that becomes the costume in the play."

Play is the word he comes back to again and again. Walker grew up in Dorset, part of a nuclear family (mother, father, brother), spent his childhood poring over the pages of Tintin books, and playing outdoors. The picture he paints of it is coloured in happiness. You can see that childhood in his photographs, in their lightness, their sense of fun, their creamy, sun-dappled full fatness. "I think there are aspects of being a child that are too good to lose as you grow up. And I think that being a photographer allows me to still look at things with wonder. It's a total high I get."

Right now Walker is sitting in his studio in "very inner city" London, looking out at six tower blocks. But he's talking about Maurice Sendak (whose In The Night Kitchen inspired that baguette plane) and the films of Powell and Pressburger and the photographs of Cecil Beaton; in short all the things that have informed his work.

All actions have equal and opposite reactions. It's not just a rule in science. You can see it at work in music and fashion. Fashion photography too. If the nineties belonged to the grungey images of Corinne Day (models with dirty fingernails), Walker came along around the millennium to reconfigure the form and returned it to a state of innocence. From bad romance to high romance if you like.

And his is a quintessentially British romance – romanticism might work better – at that. "I don't go about being British," he argues when I suggest as much. "It's not an aim of mine. I recognise the word pantomime in my work and that's an exclusively British thing, I think. But it would be a lie to say I thought about it. It just seeps out."

Tim Walker's requirements for a 2005 shoot:

80 white rabbits

20 ballerinas

17 mirrored geese

250 ostrich eggs (sprayed gold)

1 box of giant hands

20 Christmas trees

1 Rolls-Royce

The Tim Walker story goes something like this. Some time after he read Tintin he started reading fashion magazines in his late teens and was hooked. "I could see that fashion photography was probably the only way one could tell a story. The whole idea of a fantastical story had its place in fashion photography. That was the only place you could do it. It allowed it. I used to look at fashion pictures and I thought, 'Well, I really quite like that world.'"

He borrowed his brother's camera, a little snap camera, a Christmas present. But he didn't think he could be a proper photographer because he struggled to get to grips with the technicalities. Still, he persevered. He got himself an internship at Vogue House, looking through the archives. "I thought it was actually the dud job working in the dungeon of Conde Nast. I wanted to be in the bright lights and the studio and see all the action. But actually that was the godsend because that was the opening of the door to the history of fashion photography."

Among the "hundreds and hundreds" of photographers he discovered Cecil Beaton stood out. He noticed Beaton's "playful eye" and his willingness to muck about with paper and tinfoil and backdrops – the same things Walker would come to do. He recognised in Beaton a fellow traveller.

Walker started getting some studio experience working for Nick Knight and even spent time as Richard Avedon's fourth assistant. Was there a fifth assistant? "No, I was bottom of the rung. All the crappy, menial jobs all sunk down the ladder. So I opened the studio in the morning and closed it at night. But it was an invaluable lesson in how a photographer communicates with a sitter. Avedon was a master of communication. And it wasn't a sort of Austin Powers communication – sexy and hand-on-hip and 'give it to me, baby'. It was much more visual. Two models would come into the studio and they'd both be wearing black suits and he'd go, 'You're two black crows sitting on a branch and the branch has fallen.' He'd give them stories to play out that I think in the end make his stories so memorable.

"People are very awkward about having their picture taken. I am, you are, we all are. We hate it and anyone who likes it, you wouldn't want to take their picture. It's the responsibility of the photographer to give that person a scenario. If you're told to be a black crow it's something we can all understand and all perform."

Maybe. Later, Walker will nuance the idea when we're talking about his image of a UFO (containing a model) joining a fox hunt. "We photographed that in Northumberland. We spent ages rigging it and scaffolding it and then hiding all the rigging behind an old wooden fence and 80 hounds. So it's all there and physical because the emotion you get from the person in the picture is real. It gives someone something to act against as well. It gives them a real stage with real scenery to do their performance on."

And that is why he goes to so much trouble, goes to such great lengths (like constructing a baguette plane out of polyester). He's telling a story and he wants you to believe it.

Tim Walker is 40 now. He's not grown up but he is growing, he thinks. Looking through the pictures that make up Story Teller he sees in his own work not only a growing confidence in portraiture but a shadowier quality coming through too. "I think it's a lot darker," he admits. That's true. Whereas an earlier collection of his photographs (simply called Pictures) was all fairy cakes and head-over-heels, Story Teller is at times black lace and spiders. Less Stella McCartney, more Mary Shelley. "I don't know where that is coming from. I don't know if it's maturity. I've always been drawn to the poetry of darker things and I think maybe there's a maturity in me now being 40 where I feel confident enough to deal with it and talk about it visually. The idea of the dying poet and that whole concept of gothic-ness is something I find very beautiful."

He was hoping to bring that dark beauty out by adapting Iain Banks's neo-gothic debut novel The Wasp Factory. "That's a major desire and a major disappointment because the rights to the book are no longer with Iain Banks. They've been passed along, along and along. I've met the people who own it and they're not prepared to make the film yet. Unfortunately. And it's something I could totally visualise and would love to have got involved with for a couple of years, but it's not to be. So at the moment I'm looking at other ideas. I'm reading like a bookworm."

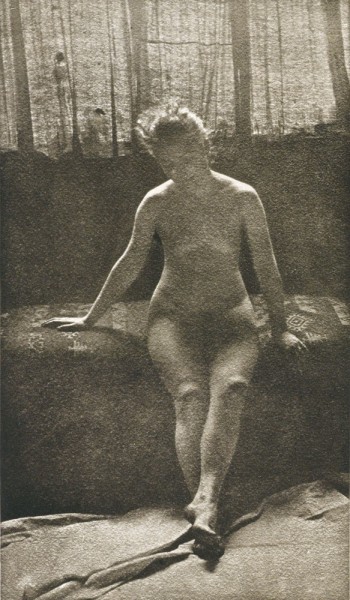

That feels like an appropriate image for Walker. From his photographs you do get the sense of a bookish teenager who is going through growing pains. In Story Teller there's even a hint of a burgeoning sexuality. For the first time there's a hint of a different kind of play in his pictures. For the first time in his photographs there are bare breasts and a batwing of desire. It's just that they're mixed in with giant snails and the like. "I think in the original book the pictures had no sexuality whatsoever. Because in a way it's the eye of a child looking at an adult. I think sexuality was something I didn't want to do. But I think this book – although it's not overflowing with sexuality – is the beginnings of the suggestion of something. And that's a growing up in some way. But the whole idea of sexuality in photography is something I can't enforce on somebody unless I see it in them."

He starts talking about the only nude in the book, a portrait of the Polish model Malagosia Bela lying face down on a bed (beside said giant snail) wearing only red patent-leather shoes. "With someone like Malagosia, that's a portrait of her because she's very comfortable with herself in that way. That is her. So it was very easy for me to do a picture of her nude. As it was with Kate Moss the other day. She's very comfortable so to do a picture of her in the nude is a genuine thing. I would never ever push sexuality or nudity on someone if it wasn't them."

We talk about this for a while, because, I suppose, I'm fascinated by how distant his visual world is from, say, the fashion photographer Helmut Newton, who built his career on playing with pornographic tropes. Walker tells me he was just watching a documentary about Newton. "I was fascinated by the sexuality in his pictures. I was fascinated to know whether the girls who work in my studio find them offensive, which they don't. They find them playful and humorous. And just to hear Newton talk about how he had this daydream of a girl masturbating on the side of a car, leaning into the tailfin of a Buick. He had this whole fantasy and it was so genuine. Helmut Newton was comfortable enough to reveal to the world that he had that fantasy, and not only was he comfortable enough to talk about it, but he was comfortable enough to document it as a fantasy picture. That sort of truthfulness I find very appealing. It's just not something I fantasise about. For Helmut Newton his fantasy was nudity. My fantasy might be a bread aeroplane."

For Tim Walker those childhood summers still stretch on for ever.

Tim Walker Story Teller is published by Thames & Hudson

www.timwalkerphotography.com